Loss of vital forests in the tropics increased by 12 percent between 2019 and 2020, a satellite-based survey found.

By Chris Mooney, Brady Dennis and John Muyskens

The loss of forests critical to protecting wildlife and slowing climate change accelerated during 2020, despite a worldwide pandemic that otherwise led to a dramatic drop in greenhouse gas emissions, a global survey released Wednesday has found.

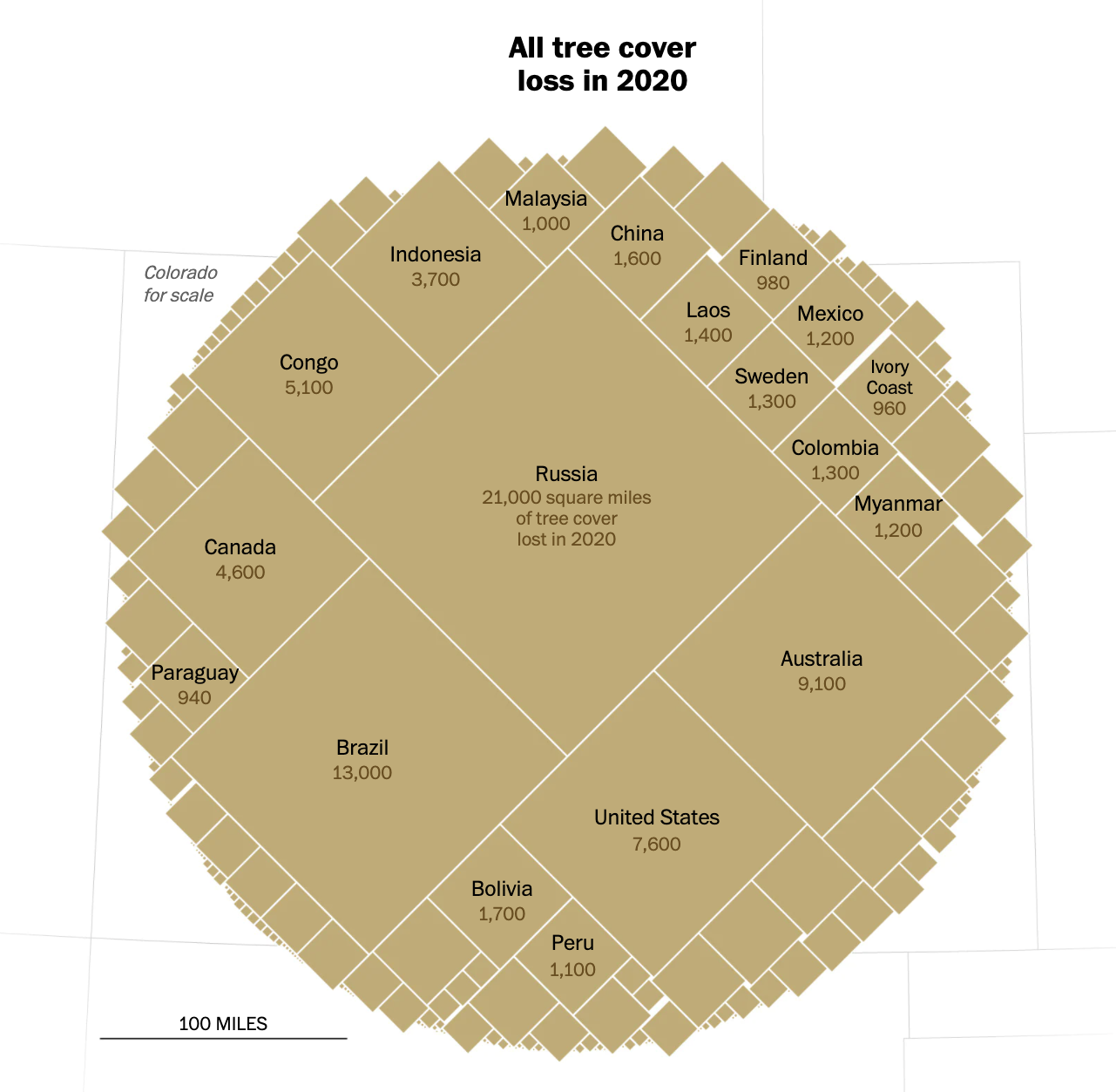

The Earth saw nearly 100,000 square miles of lost tree cover last year — an area roughly the size of Colorado — according to the satellite-based survey by . The change represents nearly 7 percent more trees lost than in 2019.

Source: Global Forest Watch

The vital, humid primary forests of the tropics, which store immense amounts of carbon, saw even greater devastation. More than 16,000 square miles of these forests vanished last year, a 12 percent increase, the survey found.

“It’s shocking to see forest loss increasing despite the covid crisis and the restrictions in many areas of life,” Simon Lewis, professor of global change science at University College London, said in an interview.

The shrinking of the world’s forests in 2020 had many causes, including massive wildfires in Russia, Australia and the United States, as well as droughts and insect infestation.

In the tropics, meanwhile, the key drivers were uncontrolled fires and the expansion of agriculture.

Brazil, which is home to much of the sprawling Amazon rainforest, saw the most tropical forest disappear, largely because of wildfires and the clearing of land, much of it illegally. The nation lost a swath of old-growth forest in 2020 larger than the state of Connecticut.

The findings suggest the world is headed in precisely the wrong direction if the goal is to rapidly reduce global carbon emissions and mitigate climate change. All those felled trees in primary tropical forests contributed the equivalent of 2.6 billion tons of carbon dioxide emissions to the atmosphere, Global Forest Watch estimates.

“Every year, we ring the alarm bell, but we’re still losing forests at a rapid clip,” said Frances Seymour, a distinguished senior fellow at the World Resources Institute, which launched Global Forest Watch, a collaboration with numerous partner organizations.

The new figures do not necessarily represent permanent deforestation, especially outside the tropics. Many of the areas that vanished in 2020, such as those lost to wildfires, are expected to grow back. Forested plots cut down in managed tree plantations are also not permanent losses.

Nevertheless, much of the destruction in the vital forests of the tropics stems from agricultural growth for crops like soy and cattle ranching, which is usually permanent. In Brazil, for instance, the new data details a troubling expansion within the infamous “arc of deforestation” in the southern Amazon.

From the perspective of the atmosphere, the erasure of forests has an immediate climate impact because carbon dioxide, the leading greenhouse gas, is released if the wood is burned or left to decompose. But the loss of trees also has longer-term implications, because even if vegetation returns, it may not absorb carbon as before. Some scientists fear that the warming climate, for instance, could , permanently lowering their carbon-storing potential.

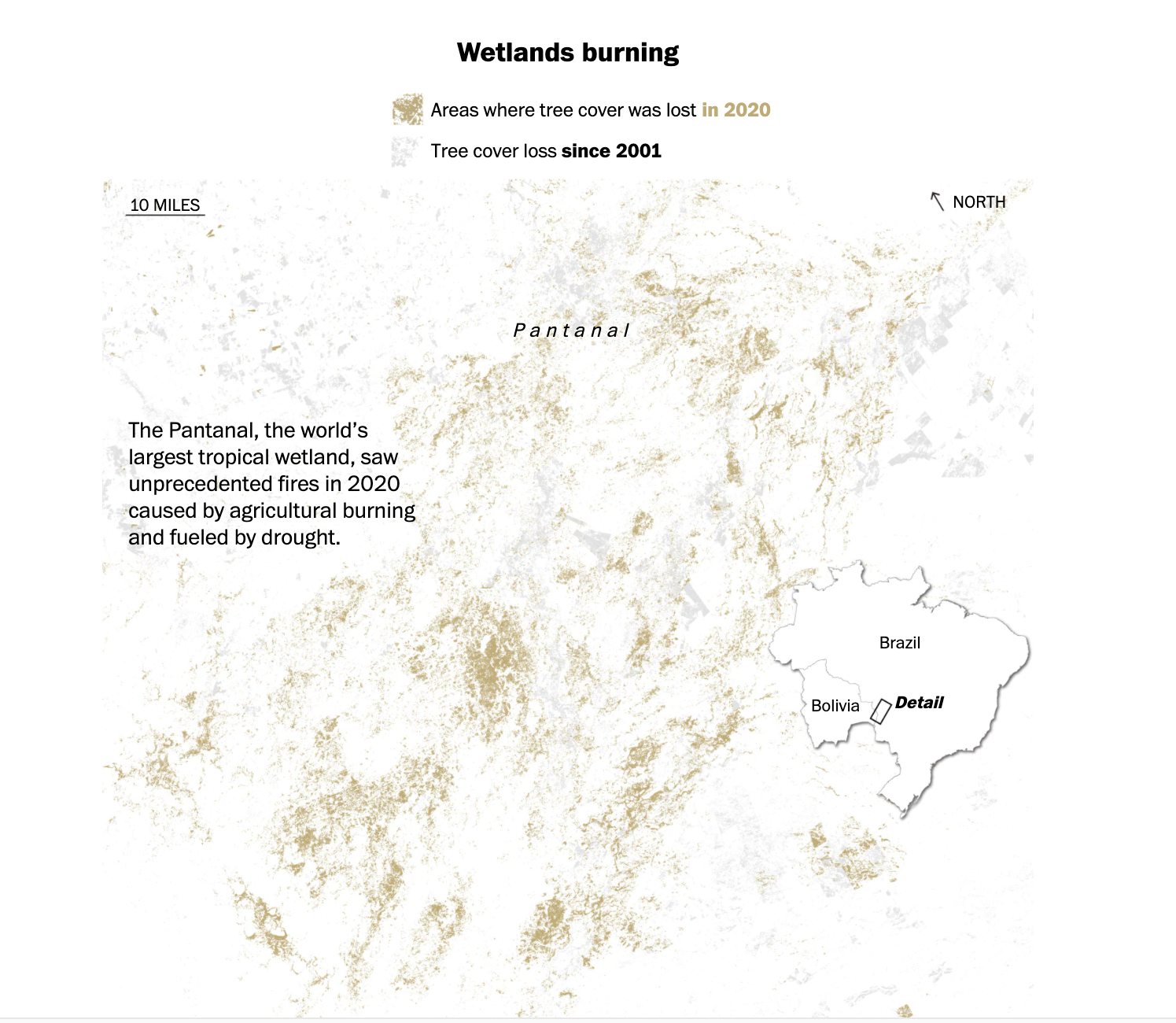

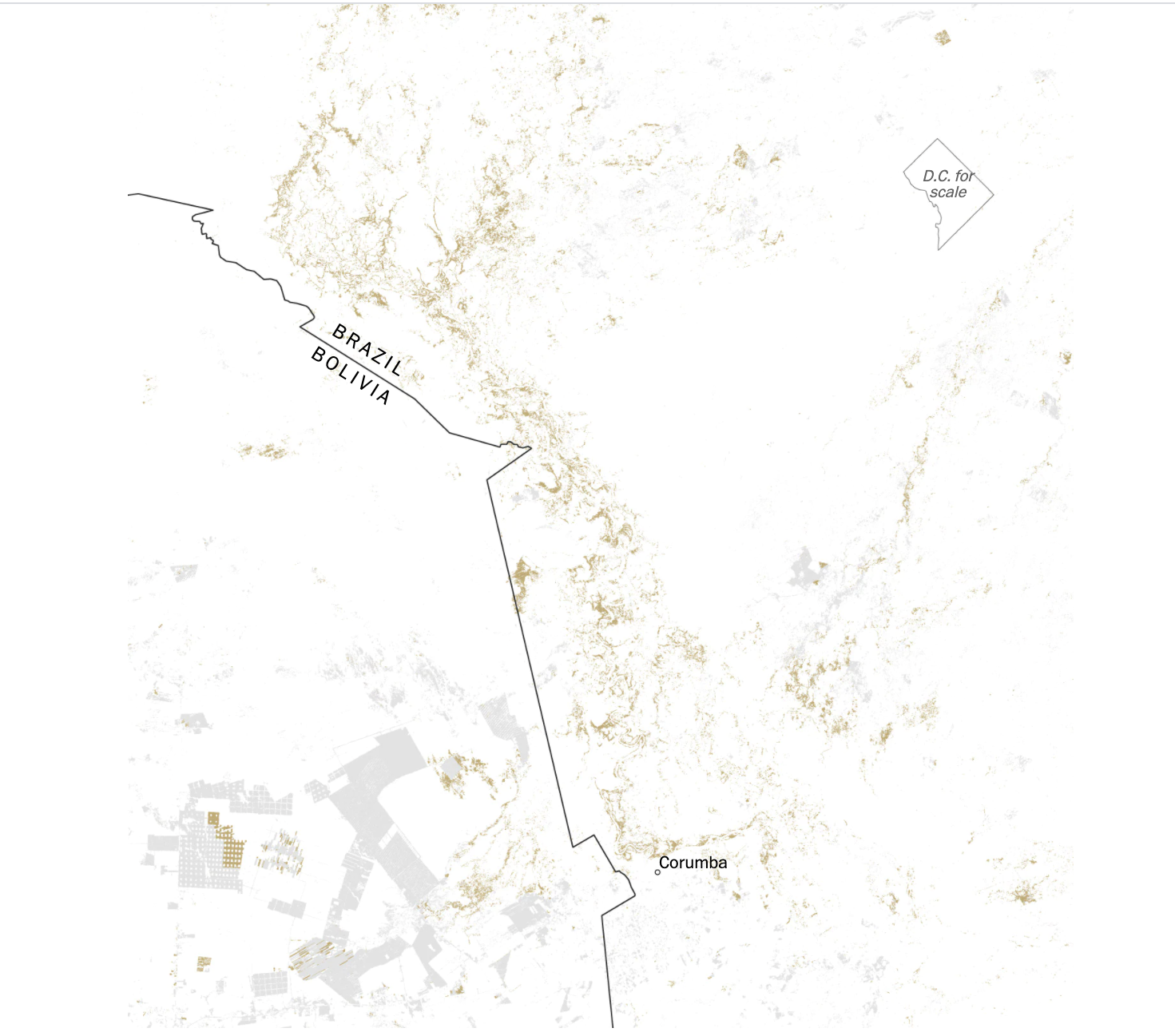

In the Amazon and other parts of Brazil, wildfires don’t generally occur naturally, at least not on a large scale. They often occur when humans light blazes to clear land, but then cannot control them. In Brazil’s enormous western wetland region known as the Pantanal, out-of-control fires consumed a staggering 30 percent of the peat-rich land in 2020, triggering intensive carbon emissions to the atmosphere.

“You don’t get the ignitions without the humans,” Deborah Lawrence, a professor at the University of Virginia who studies the links between tropical deforestation and climate change, said in an interview.

Yet there is also concern that a warming planet is changing forests in a way that worsens blazes, and that might account for some of the extreme fires that have recently ravaged Russia, Australia and parts of the United States.

“The increase in fire and disturbances is the part that’s much harder to control,” said Richard Houghton, an expert on forest losses at the Woodwell Climate Research Center in Massachusetts. “So if that’s going up, that’s no good.”

Still, there are glimmers of hope in Wednesday’s numbers, at least for some regions of the world.

Indonesia saw in 2015, for instance, as human-lit fires consumed drained peatlands, which store gigantic amounts of carbon. Since then, however, government policies have helped curb emissions and better protect the nation’s forests, and the country has seen a steady decline in tree cover losses for a fourth straight year.

By contrast, Brazil saw high levels of forest loss in the mid-2000s, but an international soy moratorium and other corrective actions by officials there drove forest loss down for almost a decade. Now, the problem has surged back near the levels that caused such concern to begin with.

“What governments do matters,” said Lewis, an expert on tropical forests, adding that deforestation is not inevitable and depends greatly on public policy. “Countries could get hold of deforestation rates and drive them down. It’s possible. It’s within our grasp.”

Congo, which houses the majority of the world’s second-largest tropical rainforest, also showed the second-highest level of forest losses in the tropics during 2020. Losses there have risen steadily for a decade, driven by small-scale local clearing of land for agriculture and firewood. Scientists fear the potential forest losses in the vast Congo basin have only begun.

This is all happening as the world is supposed to be using its forests as a key weapon in the fight to slow the Earth’s warming. If forests continue to shrink, so does the chance to limit warming to 1.5 Celsius (2.7 Fahrenheit) compared to preindustrial levels — that’s the point beyond which scientists warn of increasingly profound environmental damage.

“It’s a critical part of keeping temperatures below 1.5 C,” Lewis said. “Restoring tropical forests is one of the most efficient ways of removing carbon dioxide and slowing climate change.”

In a massive report published in 2019, the United Nation’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in helping to combat climate change.

“Reducing deforestation and forest degradation lowers [greenhouse gas] emissions,” the authors wrote, noting that protecting forests could mitigate up to 5.8 billion tons of carbon dioxide emissions each year. “By providing long-term livelihoods for communities, sustainable forest management can reduce the extent of forest conversion to non-forest uses (e.g., cropland or settlements).”

Accomplishing that in a warming world with a growing population will require increasing the efficiency of food production on existing land, Lewis said. “The global footprint of agriculture needs to be limited to the land that’s already under agriculture,” he said, adding that means reducing food waste and shifting human diets to include less meat and dairy products.

The more forest that gets cut down or burned, the more the world loses its ability to have forests pull carbon from the atmosphere — not to mention the loss of old-growth trees that have locked away carbon for generations, Lawrence said.

“We cannot lose that stock,” said Lawrence, who refers to forests as a “carbon sequestering machine.” “If we don’t lose them, we still have to work really, really hard [to cut global emissions]. If we do lose them, I don’t think we can make it.”

Conversations about how to slow and avoid deforestation have been happening for a very long time among world leaders, but the problem persists. “And still, we are losing tropical forest,” she said. “And that is just sad.”

The most obvious solution would be to widely tax greenhouse gas pollution, she said. “A price on carbon is essential,” she said.

Like other experts, Lawrence said it is difficult to overstate how hard it will be for the world to meet its climate targets without a huge assist from forests.

“It gives me a pit in my stomach, because I don’t think we can do it,” she said. That is, unless deforestation is brought under control. “The science says these forests are terribly important. I also love these forests, and I want to see them stay.”

Source:

Related to SDG 13: Climate action