By Patrick Greenfield

Animal populations have plunged an average of 68% since 1970, as humanity pushes the planet’s life support systems to the edge

Mass soybean harvesting in Campo Verde, Brazil. Intensive agricultures has contributed to the collapse of some animal populations. Photograph: Alffoto/WWF

populations are in freefall around the world, driven by human overconsumption, population growth and intensive agriculture, according to a major new assessment of the abundance of life on Earth.

On average, global populations of mammals, birds, fish, amphibians and reptiles plunged by 68% between 1970 and 2016, according to the WWF and Zoological Society of London (ZSL)’s biennial . Two years ago, .

The research is one of the most comprehensive assessments of global biodiversity available and was complied by 134 experts from around the world. It found that from the rainforests of central America to the Pacific Ocean, nature is being exploited and destroyed by humans on a scale never previously recorded.

The analysis tracked global data on 20,811 populations of 4,392 vertebrate species. Those monitored include high-profile threatened animals such as pandas and polar bears as well as lesser known amphibians and fish. The figures, the latest available, showed that in all regions of the world, vertebrate wildlife populations are collapsing, falling on average by more than two-thirds since 1970.

Robin Freeman, who led the research at ZSL, said: “It seems that we’ve spent 10 to 20 years talking about these declines and not really managed to do anything about it. It frustrates me and upsets me. We sit at our desks and compile these statistics but they have real-life implications. It’s really hard to communicate how dramatic some of these declines are.”

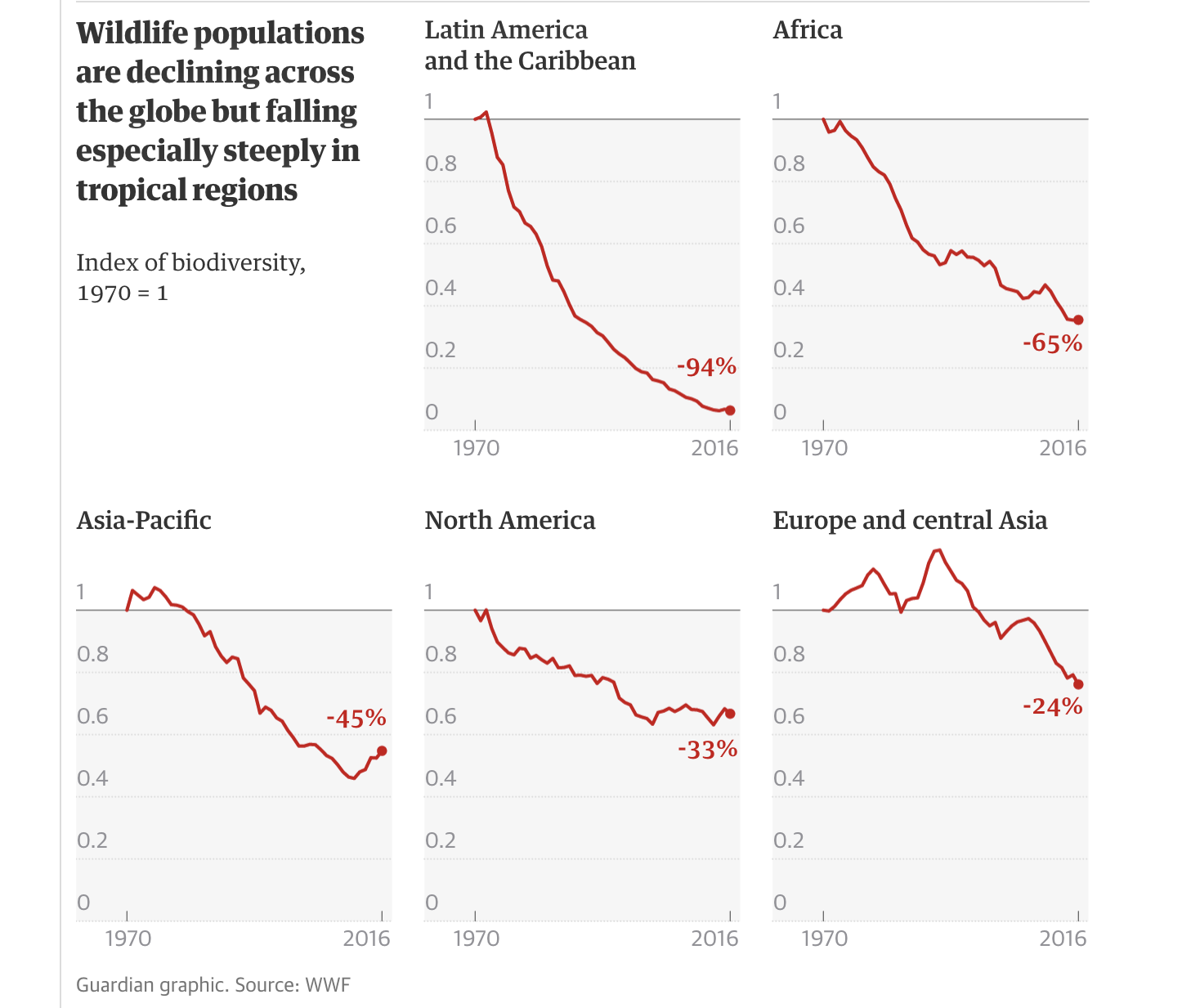

Latin America and the Caribbean recorded the most alarming drop, with an average fall of 94% in vertebrate wildlife populations. Reptiles, fish and amphibians in the region were most negatively affected, driven by the overexploitation of ecosystems, habitat fragmentation and disease.

Africa and the Asia Pacific region have also experienced large falls in the abundance of mammals, birds, fish, amphibians and reptiles, dropping 65% and 45% respectively. Europe and central Asia recorded a fall of 24%, while populations dropped 33% on average in North America. To form the (LPI), akin to a stock market index of wildlife, more biodiverse parts of the world, such as tropical regions, are given more weighting.

A tiger in Bardia national park, Nepal, a species that is showing signs of recovery. Photograph: Emmanuel Rondeau/WWF

Experts said the LPI was further evidence of the sixth mass extinction of life on Earth, with because of human activity, according to the UN’s global assessment report in 2019. Deforestation and the conversion of wild spaces for human food production have largely been blamed for the destruction of Earth’s web of life.

The report highlights that 75% of the Earth’s ice-free land has been significantly altered by human activity, and almost 90% of global wetlands have been lost since 1700.

Mike Barrett, executive director of conservation and science at WWF, said: “Urgent and immediate action is necessary in the food and agriculture sector. All the indicators of biodiversity loss are heading the wrong way rapidly. As a start, there has got to be regulation to get deforestation out of our supply chain straight away. That’s absolutely vital.”

Freshwater areas are among the habitats suffering the greatest damage, according to the report, with one in three species in those areas threatened by extinction and an average population drop of 84%. The species affected include the critically endangered Chinese sturgeon in the Yangtze River, which is down by 97%.

Using satellite analysis, the report also finds that wilderness areas – defined as having no human imprint – only account for 25% of the Earth’s terrestrial area and are largely restricted to Russia, Canada, Brazil and Australia.

Matécho Forest in French Guiana. Rainforests around the world are subject to overexploitation. Photograph: Roger Leguen/WWF

Tanya Steele, chief executive at WWF, said: “We are wiping wildlife from the face of the planet, burning our forests, polluting and over-fishing our seas and destroying wild areas. We are wrecking our world – the one place we call home – risking our health, security and survival here on Earth.”

Sir David Attenborough said that humanity has entered a new geological age – the anthropocene – where humans dominate the Earth, but said it could be the moment we learn to become stewards of our planet.

“Doing so will require systemic shifts in how we produce food, create energy, manage our oceans and use materials. But above all it will require a change in perspective,” he wrote in a accompanying the report.

“The time for pure national interests has passed, internationalism has to be our approach and in doing so bring about a greater equality between what nations take from the world and what they give back. The wealthier nations have taken a lot and the time has now come to give.”

A dead shark surrounded by litter on the beach at Hann in Dakar. Photograph: Seyllou/AFP/Getty Images

While the data is dominated by the decline of wildlife populations around the world, the index showed that some species can recover with conservation efforts. The blacktail reef shark in Australia and Nepalese tiger populations have both shown signs of recovery.

ZSL research associate Louise McRae, who has helped compile the LPI for the last 14 years, said: “Whilst we are giving a very depressing statistic, all hope is not lost. We can actually help populations recover.

“I feel frustrated by having to give a stark and desperate message but I think there’s a positive side to it as well.”

A separate says that at least 28 bird and mammal extinctions have been prevented by conservation efforts since the came into force in 1993.

Source:

Related to SDG 13: Climate action and SDG 15: Life on land